Sulfur Cinquefoil or Rough-fruited Cinquefoil, Potentilla recta, is native to Eurasia, probably originating in the Mediterranean. The plant was introduced to North America where it has thrived.

Sulfur Cinquefoil or Rough-fruited Cinquefoil, Potentilla recta, is native to Eurasia, probably originating in the Mediterranean. The plant was introduced to North America where it has thrived.

Monthly Archives: February 2014

Yarrow—Edible Weeds

It is important to refer to guidebooks or local foraging experts to identify plants. Please look at our posts as starting points, not as definitive references on plants.

Yarrow, Achillea millefolium, is well known as a medicinal herb. The leaves are bitter, but can be eaten raw or cooked; we put young leaves in a smoothies with other greens. We use the flowers to make tea as well as a vodka tincture we add to tea. For bug bites and cuts, we make a tincture with the flowers and leaves.

Yarrow, Achillea millefolium, is well known as a medicinal herb. The leaves are bitter, but can be eaten raw or cooked; we put young leaves in a smoothies with other greens. We use the flowers to make tea as well as a vodka tincture we add to tea. For bug bites and cuts, we make a tincture with the flowers and leaves.

Lamb’s-Quarters—Edible Weeds

It is important to refer to guidebooks or local foraging experts to identify plants. Please look at our posts as starting points, not as definitive references on plants. Some medical conditions can be complicated by wild plants.

Lamb’s-quarters, Chenopodium album, also known as pigweed, goose foot, and wild spinach, has edible leaves and seeds. While the leaves can be eaten raw, it is not recommend to eat large quantities as the leaves contain saponins. Cooking reduces these. Cooking also reduces the oxalic acid content. The leaves can be harvested from mid-spring into the fall.

Lamb’s-quarters, Chenopodium album, also known as pigweed, goose foot, and wild spinach, has edible leaves and seeds. While the leaves can be eaten raw, it is not recommend to eat large quantities as the leaves contain saponins. Cooking reduces these. Cooking also reduces the oxalic acid content. The leaves can be harvested from mid-spring into the fall.

The leaves are a good spinach substitute. We add fresh leaves to salads and smoothies. We dry or freeze the leaves for winter to add to smoothies. Like spinach, we steam and sauté the stems and leaves, or add them to soups. In Japan, lamb’s-quarter is also recognized as an edible wild plant. The young leaves are boiled and marinated with sesame seed or peanut butter dressings.

The seeds are very nutritious and can be ground into flour. We have found the seeds to be really small and difficult to harvest. The seeds aren’t wasted: our population of wild birds love them.

White Clover—Edible Weeds

White clover, Trifolium repens, has its flowering head on separate stalks from its leaves. We make tea from the flowers of a variety of clover in our garden. We have found the white clover to be the sweetest. We also add the flower to salads and smoothies.

White clover, Trifolium repens, has its flowering head on separate stalks from its leaves. We make tea from the flowers of a variety of clover in our garden. We have found the white clover to be the sweetest. We also add the flower to salads and smoothies.

Before the clover flowers, the young leaves can be used in salads and soups, but we find them too bitter. We have heard that the dried leaves can be used as a vanilla substitute for baking—something we wish to try this summer.

Our Winter Chickadees

The black-capped Chickadee, Parus atricaillus, is found though out the Northern US from Alaska to Maine. It is the Maine State bird—you see the image of these amazing animals on the our car license plates. They get their name from their call: chick-a-dee-dee-dee. A tame and inquisitive bird, they can get very protective of their garden and are quite vocal when they think you should not be there.

The black-capped Chickadee, Parus atricaillus, is found though out the Northern US from Alaska to Maine. It is the Maine State bird—you see the image of these amazing animals on the our car license plates. They get their name from their call: chick-a-dee-dee-dee. A tame and inquisitive bird, they can get very protective of their garden and are quite vocal when they think you should not be there.

A Chickadee is about 4.75–5.75 in. (12–15 cm) in length, and 0.35–0.42 oz. (10–12 grams) in weight. These birds spend the entire year in Maine, including the winter. To survive the cold, the Chickadee needs to feed during the day to gain fat to use through the night for energy. But with very precious fat reserves, they drop their body temperature by 17°F–21°F (10°C–12°C) to conserve that energy while they sleep. Their plumage is also a far more efficient insulator than on many birds their size. Chickadees do not build winter shelters, but find small places to roost overnight—their tails can appear bent from spending the night in a cramped spot. Naturally, our (their?) bird feeders are never without a Chickadee this time of year.

Cycles of Life—Canyon de Chelly

Time & Space—Canyon de Chelly

Canyon de Chelly is a layered tapestry in time and space. The rock ledge in the bottom left corner of the image is about 100ft/30m below me. The canyon floor is several hundred feet more. Cottonwood trees, with their bright autumn foliage, mark water running below the surface of the land. Paths and roads trace the passage of the residents, human and animal.

Canyon de Chelly is a layered tapestry in time and space. The rock ledge in the bottom left corner of the image is about 100ft/30m below me. The canyon floor is several hundred feet more. Cottonwood trees, with their bright autumn foliage, mark water running below the surface of the land. Paths and roads trace the passage of the residents, human and animal.

Stone & Symbols—Canyon de Chelly

The canyon walls are sliced from De Chelly sandstone. Formed during the late Permian Period, about 200 million years ago, the stone still reflects the ancient sand dunes that created them.

The canyon walls are sliced from De Chelly sandstone. Formed during the late Permian Period, about 200 million years ago, the stone still reflects the ancient sand dunes that created them.

The walls also are a canvas for petroglyphs, images and symbols chipped into the stone. Petroglyphs are difficult to date. Both the Anasazi and Dineh (Navajo) practiced this art. These images can commemorate an event, mark a trail, or hold deep spiritual or religious significance in rites or initiations. This section of the canyon wall near Antelope House Ruin has petroglyphs scattered over its surface. Click on the image for a larger view.

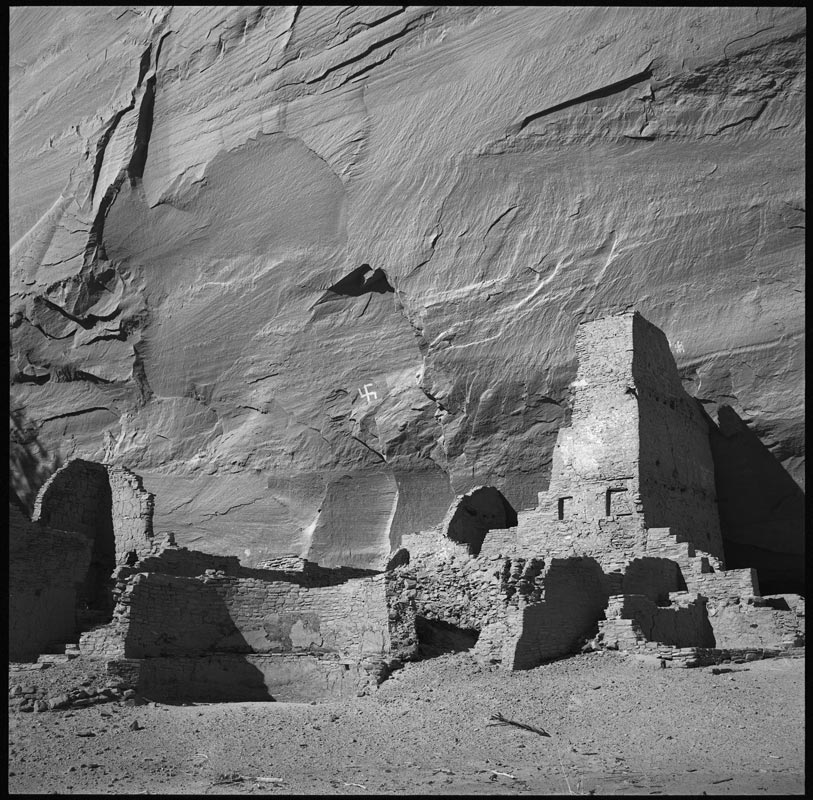

Antelope House Ruin—Canyon de Chelly

Before the Dineh, or Navajo, arrived in Canyon de Chelly, the area was home to the Anasazi, a name given to them by the Dineh meaning “ancestors of the enemy.” The Anasazi settled the area sometime in the first century.

Before the Dineh, or Navajo, arrived in Canyon de Chelly, the area was home to the Anasazi, a name given to them by the Dineh meaning “ancestors of the enemy.” The Anasazi settled the area sometime in the first century.

Antelope House Ruin is from the Great Pueblo Period or Pueblo III period, beginning around the 1100s when large settlements were being built. The two-story tower suggests these places were fortifications—some built high up on the canyon walls. The round wall at the left of the tower is the remains of a kiva that played a ceremonial or religious role in the community. Even with these large constructions, it seems that most of the population still lived in small dwellings outside these structures.

It is unclear whether the swastika on the canyon wall is from the Anasazi or Dineh. The Hopi, a descendant of the Anasazi, use this symbol as a representation of their migration story. For the Dineh, it is used in healing rituals.

By the beginning of the 1300s, the Anasazi had gone from Canyon de Chelly. Studies of tree rings shows there was a sever drought from 1276–1299. There is some evidence that over population and stress placed on the environment may have contributed to their decline as well. The modern Pueblo tribes of the Hopi, Zuni, Acoma, and Leguna are believed to be the descendants of the Anasazi.

Spider Rock, Speaking Rock—Canyon de Chelly

Spider Rock in Canyon de Chelly National Monument is one of the most recognized sites in the American Southwest. This is the spiritual and geographic center of the Dineh, also known by their common name, Navajo.

Spider Rock in Canyon de Chelly National Monument is one of the most recognized sites in the American Southwest. This is the spiritual and geographic center of the Dineh, also known by their common name, Navajo.

The tower in the center of the image is Spider Rock. This is the home of Spider Woman. She helped rid the world of monsters and gave the Dineh the gift of weaving; an art form at which these people excel.

Speaking Rock or Talking Rock is at the tip of the butte on the left on the image. The Dineh have a children’s story where it is said that Speaking Rock will tell Spider Woman which children have been naughty. Spider Woman will take these children to her rock and eat them. The paler colored rock at the top of her tower is thought to be the bleached bones of these unfortunate kids.

Canyons are cut from plateaus. We are really not looking at tall features, but deep ones. The canyon floor is about 1,000ft/300m below the rim at this point. If you look at the horizon near the center of the panorama, you can see a mountain called Black Rock. That is a volcanic plug; the core of a volcano which is left after the sides have been eroded away.

Click on the image for a larger view.