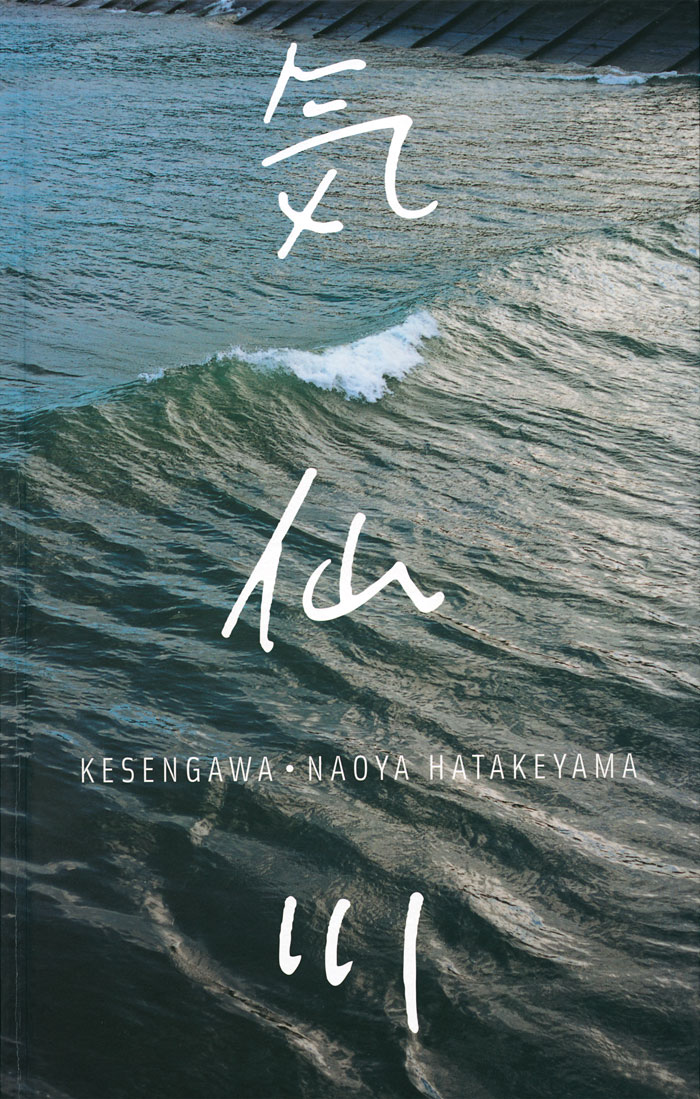

A French edition of Kesengawa by Japanese photographer Naoya Hatakeyama was released in 2013. While based on the 2012 Japanese edition and designed by the same designer, Seiichi Suzuki, this volume is not simply a reissue. Despite first impressions, it is not a simple book. Not all its secrets are readily available—some cultural references will be more obvious to Japanese—but neither is it obscure. Kesengawa has rewards for those that slow down and take time.

A French edition of Kesengawa by Japanese photographer Naoya Hatakeyama was released in 2013. While based on the 2012 Japanese edition and designed by the same designer, Seiichi Suzuki, this volume is not simply a reissue. Despite first impressions, it is not a simple book. Not all its secrets are readily available—some cultural references will be more obvious to Japanese—but neither is it obscure. Kesengawa has rewards for those that slow down and take time.

On March 11th, 2011, Northeastern Japan, Tohoku, suffered a huge earthquake followed by an unimaginably devastating tsunami. 230,000 people lost their homes and nearly 20,000 people lost their lives along 250 miles of the coast. Rikuzentakata, the photographer’s home town, was one of those places destroyed. Kesengawa, or Kesen river (the suffix -gawa means river in Japanese), flows through that town.

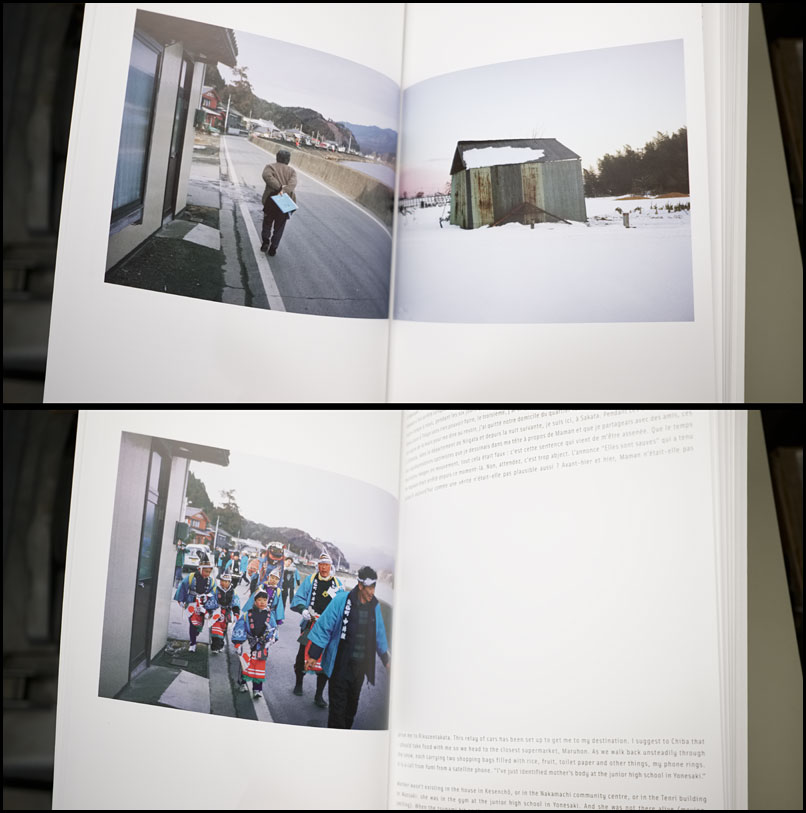

The book is split into two parts. The first has photographs Hatakeyama took between 2002 and 2010. These were never made for exhibition, simply for himself. The work has a casualness to it, part snapshot, part experimentation. Each image sits in the center of its page. Within this group of photographs is an essay, a French translation is at the top of the page and the English on the bottom. The essay reflects on Hatakeyama’s journey to his home town a couple of days after the tsunami; he had no contact with his mother or sister and decided to return to find them. The text is never presented on the same page as the photographs, but the two languages are split by a white space the size of an image. The effect is striking, as if switching between the author’s memories and his inner monolog, two states which cannot exist concurrently. This cognitive limitation is made acute by the peacefulness of the images versus the anguish of the text.

The text is never presented on the same page as the photographs, but the two languages are split by a white space the size of an image. The effect is striking, as if switching between the author’s memories and his inner monolog, two states which cannot exist concurrently. This cognitive limitation is made acute by the peacefulness of the images versus the anguish of the text.

But this section is more complex than it first appears: I highly recommend going through this book more than once. The images, mostly landscapes, create a map. Landmarks repeat. People and events allude to the community supported by this place. Each viewing creates more connections, inviting more participation. One spread shows a woman walking down a street; the author’s mother outside her home? Turn the page; the same building and road, but populated by group of festival participants. Other images seem more metaphoric. It is hard not look at images of water without premonition.

The first section ends with a blank page.

The second section has a single image across both pages of the spread. These images are different: large, detailed, and distant. The warmth found in the first section has become exacting and clinical. Hatakeyama is not facing this landscape as he did before. There is no ambiguity: this is a postmortem. At first, the totality of the destruction makes the town unrecognizable. But the traces of life found in the first section are spread through these images like clues to decipher. A tree, a building, and the ever present river slowly allows the viewer to reconstruct what was lost.

But Hatakeyama does not quite end on such a bleak note. At the back of the book, there is a single photograph. It is the same size as those in the first section, the section showing life in Rikuzentakata. The photo shows the new foundation of his mother’s house. Behind that is a group of villagers watching lanterns floating on the Kesengawa. This lantern festival is for the comfort of the souls of the departed.

Documentaries of disasters usually come off as some form of perverse entertainment, a curiosity. They lack a continuity, a reality. Hatakeyama’s work is not that. It takes its depth by being grounded in that place. It gives a glimpse—and only a glimpse, for we will never know what these survivors truly experience—of how impermanent and fragile our world is and how fast it can change. It is a reminder that the place we inhabit is a small miracle hidden within our commonplace experience.

Kesengawa by Naoya Hatakeyama

11.75″ x 7.5″, 124 pages

French Edition Published by Light Motiv

ISBN: 9782953790856

Hatakeyama talked about this and his continuing work at the Boston Museum of Art on April 22nd, 2015. This one hour lecture is well worth the time.