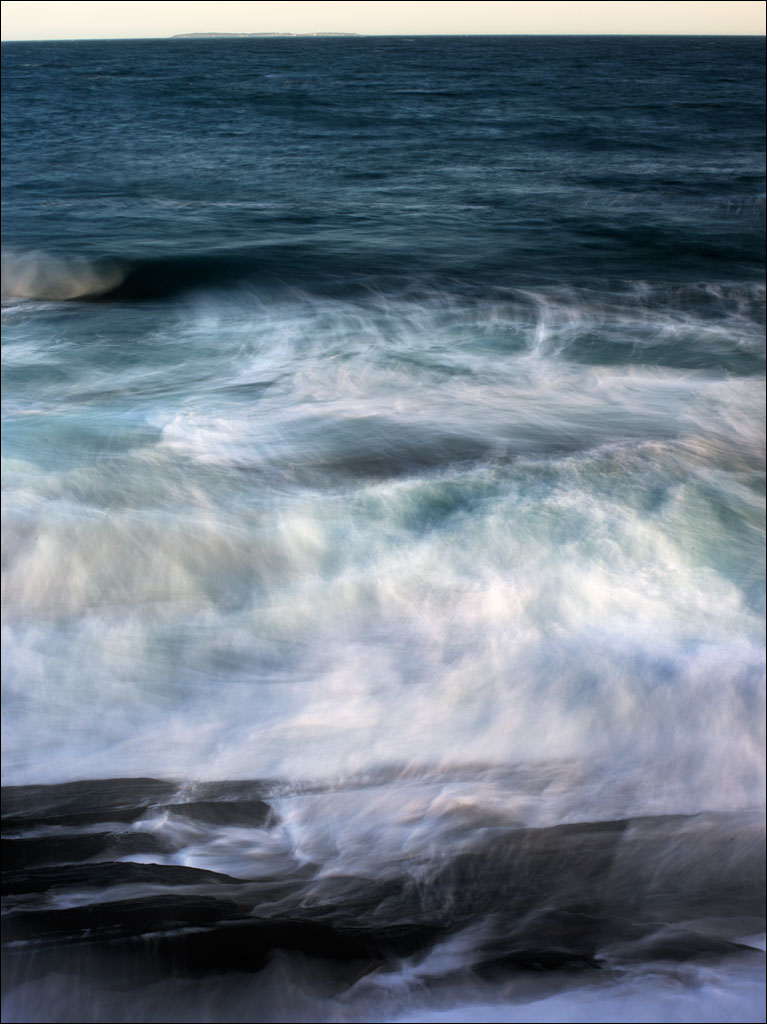

The winter has been long this year. The memories and promises of summer seem far away. The Gulf of Maine from Schoodic Point in Acadia National Park. Click on the image so summer can arrive earlier—and to make the image larger.

The winter has been long this year. The memories and promises of summer seem far away. The Gulf of Maine from Schoodic Point in Acadia National Park. Click on the image so summer can arrive earlier—and to make the image larger.

Tag Archives: Nature

Maine Winter Forest

Heaven and Earth

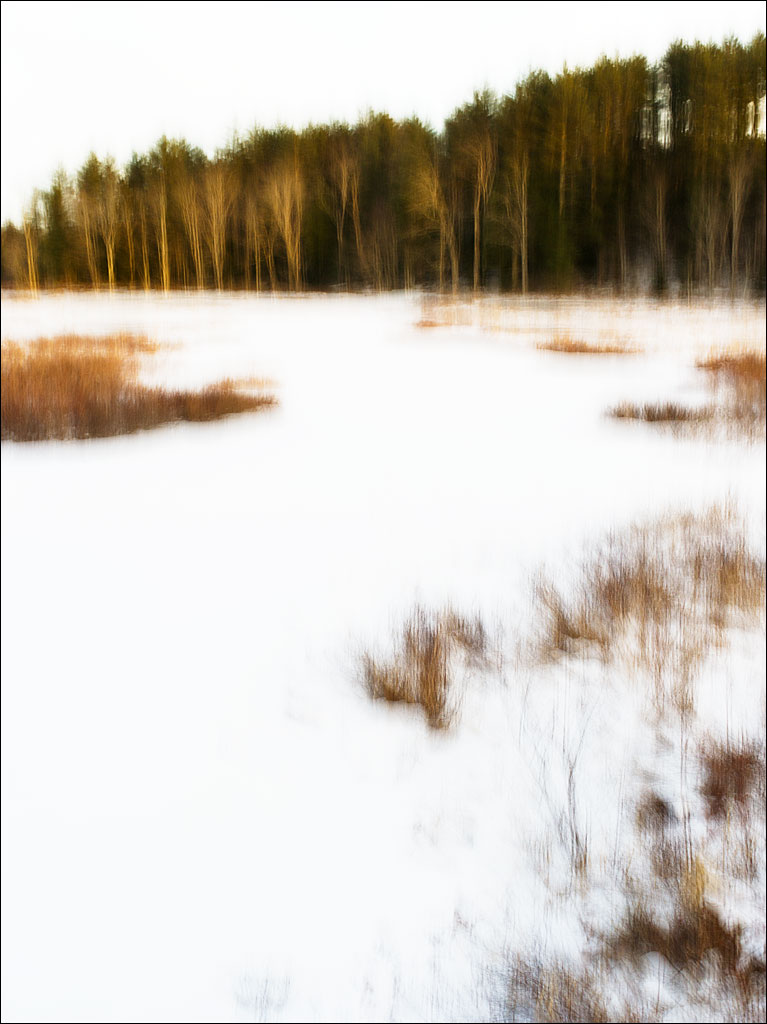

Winter Marsh

The meandering stream bed that feeds Dyer Long Pond in Jefferson, Maine is hidden beneath the snow pack. This is very different in summer. Click on image for a larger view.

The meandering stream bed that feeds Dyer Long Pond in Jefferson, Maine is hidden beneath the snow pack. This is very different in summer. Click on image for a larger view.

Winter Ocean at Pemaquid Point

Changing Seasons, Part 2

The salt marshes and dunes at Bates Morse Mountain Conservation Area are always in flux. While we like to think of the season as four monolithic blocks clearly delineating their character to the landscape, the year passes over the land with infinitely variability. No two moments are the same. Click on the image for a larger view.

The salt marshes and dunes at Bates Morse Mountain Conservation Area are always in flux. While we like to think of the season as four monolithic blocks clearly delineating their character to the landscape, the year passes over the land with infinitely variability. No two moments are the same. Click on the image for a larger view.

Changing Seasons, Part 1

Spring just does not simply arrive in Maine; snow and ice don’t simply vanish. Spring comes like a gentle kiss on the land, slowly melting away winter.

Spring just does not simply arrive in Maine; snow and ice don’t simply vanish. Spring comes like a gentle kiss on the land, slowly melting away winter.

This pond in the salt marshes of Bates Morse Mountain Conservation Area is just opening up. In a month or two, fish fry will populate the water. This pool is isolated from the rivers and streams that cut through the marsh, yet the fish population is stable. Amazingly, the salinity of the water is higher than the ocean that feeds the marsh.

Winter Woods

We had two storms in succession, on Thursday and Saturday, with another predicted for next week. Our woods are very peaceful this time of year. The drifting snow makes walking tricky as it is hard to predict whether the snow pack is a few inches deep or a few feet deep. A few of the animals that live here leave the occasion tracks, but many travel under the snow in a network of tunnels.

We had two storms in succession, on Thursday and Saturday, with another predicted for next week. Our woods are very peaceful this time of year. The drifting snow makes walking tricky as it is hard to predict whether the snow pack is a few inches deep or a few feet deep. A few of the animals that live here leave the occasion tracks, but many travel under the snow in a network of tunnels.

Sulfur Cinquefoil—Wild Flowers

Our Winter Chickadees

The black-capped Chickadee, Parus atricaillus, is found though out the Northern US from Alaska to Maine. It is the Maine State bird—you see the image of these amazing animals on the our car license plates. They get their name from their call: chick-a-dee-dee-dee. A tame and inquisitive bird, they can get very protective of their garden and are quite vocal when they think you should not be there.

The black-capped Chickadee, Parus atricaillus, is found though out the Northern US from Alaska to Maine. It is the Maine State bird—you see the image of these amazing animals on the our car license plates. They get their name from their call: chick-a-dee-dee-dee. A tame and inquisitive bird, they can get very protective of their garden and are quite vocal when they think you should not be there.

A Chickadee is about 4.75–5.75 in. (12–15 cm) in length, and 0.35–0.42 oz. (10–12 grams) in weight. These birds spend the entire year in Maine, including the winter. To survive the cold, the Chickadee needs to feed during the day to gain fat to use through the night for energy. But with very precious fat reserves, they drop their body temperature by 17°F–21°F (10°C–12°C) to conserve that energy while they sleep. Their plumage is also a far more efficient insulator than on many birds their size. Chickadees do not build winter shelters, but find small places to roost overnight—their tails can appear bent from spending the night in a cramped spot. Naturally, our (their?) bird feeders are never without a Chickadee this time of year.